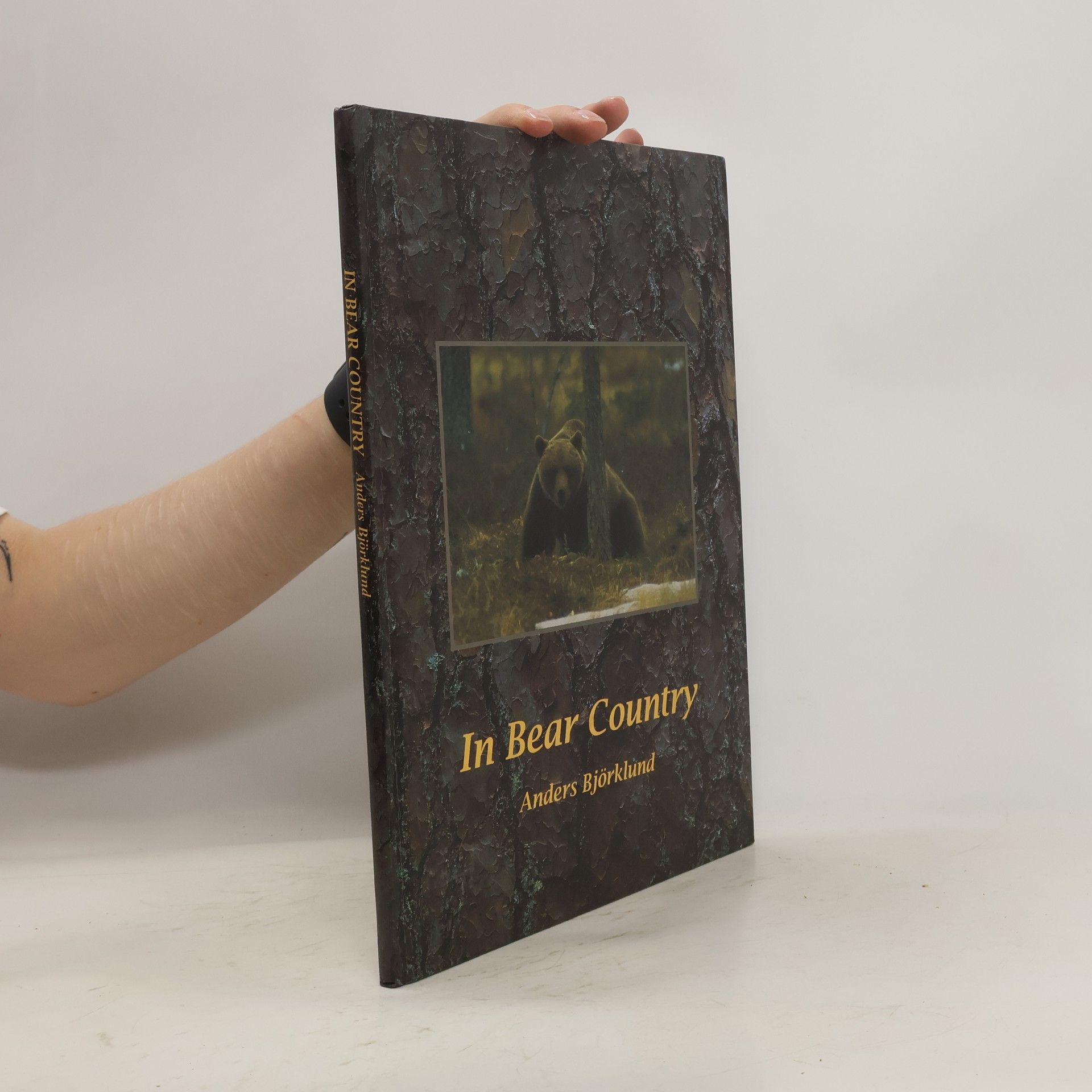

Almost 10,000 years ago the kilometer-thick continental glacier receded from northern Dalarna in central Sweden. Slowly but surely plants and animals invaded the barren grounds. The ice had left its mark on the land, especially during melting, when large amounts of moving water had changed the landscape. The animals that colonized our area came from Central Europe. Among them was the brown bear (Ursus arctos). When the ice had completely disappeared from Sweden, bears from Russia colonized Lapland, northernmost Sweden. This immigration from two directions has resulted m two genetically different lineages of brown bear in Sweden. Today there are four core areas with permanent bear populations in Sweden. The area north of the lakes Siljan and Orsasjon is a part of the southernmost bear area in the country. The bears in this southern area are not related to other bears in Sweden, but rather with bears in the Pyrenees Mountains between France and Spain. Today we have a population of about 1,000 bears in Sweden, of which about 200-300 are in the southern area. The bear, like other species, has certain requirements that its environment must provide if it is to prosper. The forests in northern Dalama and Orsa suit the bear Here is a magnificent natural area with high mountains and deep valleys, large wetlands and nature forests. The area has few people and wild animals abound. We are in Bear Country!

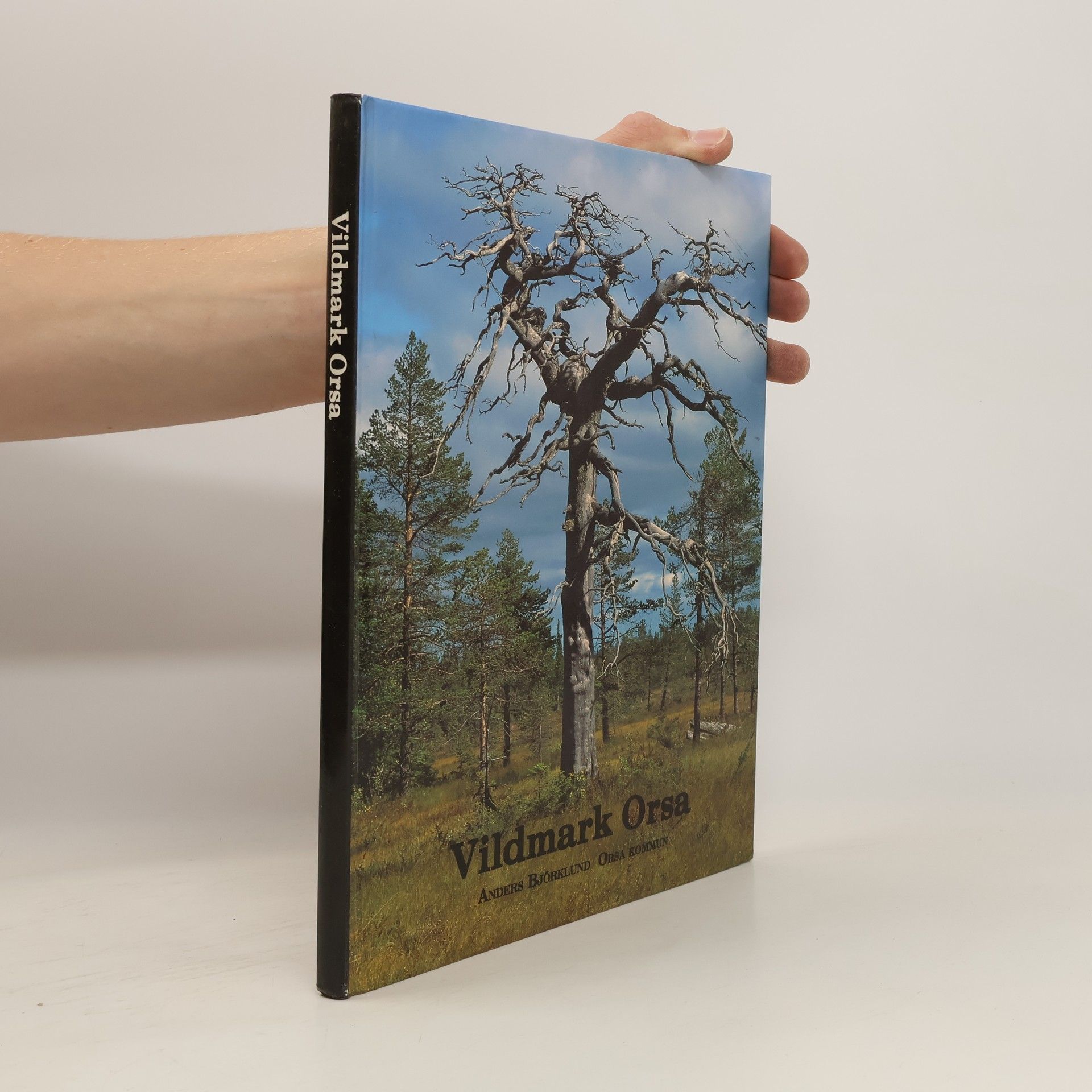

Anders Bjorklund Livres